T. Adams, J. Griffin, S. Moskowitz, B. Riley, with I. Padalecki

The profession of teaching is often associated with women; in 2019, approximately eighty percent of elementary school teachers were women.1Nancy Hoffman, “‘Inquiring after the Schoolmarm’: Problems of Historical Research on Female Teachers,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 22, no. 1/2 (1994): 105. This feminization of teaching originated in the middle of the nineteenth century. During the Market Revolution, the American economy became more market-oriented, and households became less self-sufficient. This drove an increasing number of men off farms and toward jobs that paid wages or salaries. Literacy became a required skill and teaching boys to read a necessity. In addition to performing unpaid domestic labor and childcare, women, too, felt pressure to earn income to support their families, but their options were limited by notions of gender-appropriate behavior.2Jean Boydston, “The Pastoralization of Housework,” in Women’s America: Refocusing the Past, ed. by Linda K. Kerber, et al. (New York: Oxford UP, 2016), 128.Out of these economic changes emerged the ideology of “separate spheres,” which presented women as inherently suited to maintaining households as a sanctuary from the public sphere. Women’s work generally was not considered skilled “work” to be compensated monetarily; this status was primarily reserved for work done by men (manufacturing, resource extraction, craft, and commerce).3Boydston, Pastoralization, 130.

Feminized Morality

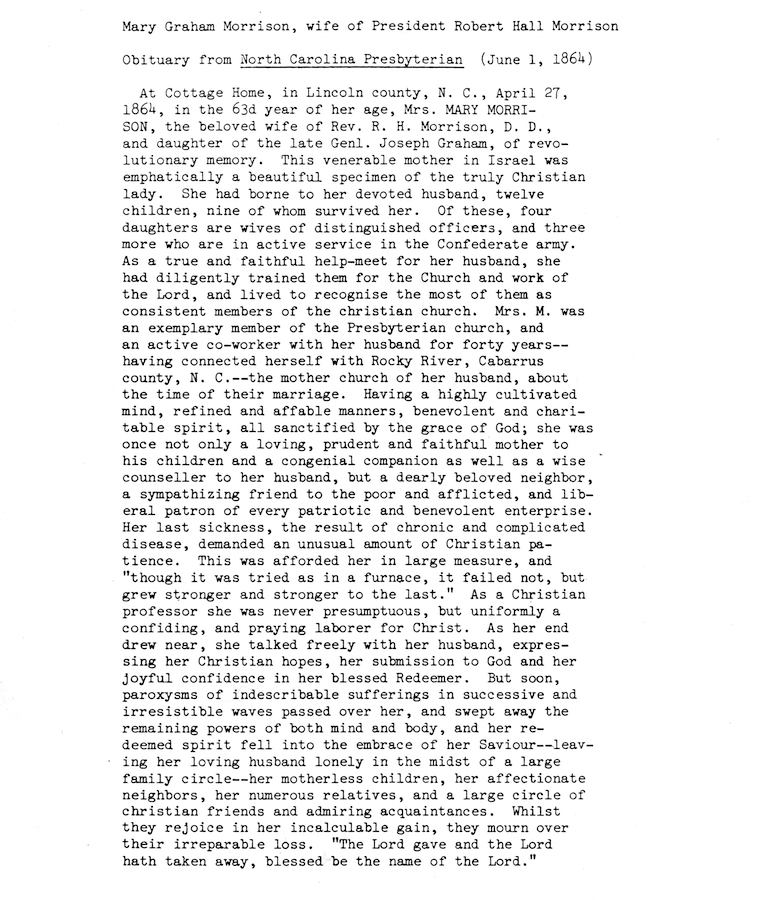

The Second Great Awakening, a period of religious revival in which many Americans developed a personal relationship with God through participation in evangelical Christianity, also shaped gender roles in the early nineteenth century. This caused an uptick in women’s participation in Protestant churches, including Presbyterianism, increasing the association of womanhood with purity and morality.4Nancy F. Cott, “Passionlessness: An Interpretation of Victorian Sexual Ideology,” Signs 4, no. 2 (1978): 227.

This was also related to the concept of Republican Motherhood, which emphasized women’s role in educating children to be virtuous and literate citizens that could participate in civic life. For literate women, teaching their children to read became another facet of their domestic responsibilities. The important duty fell mainly on mothers, again emphasizing women’s critical role as educators of their children.5Linda K. Kerber “Why Diamonds Really Are a Girl’s Best Friend: The Republican Mother and the Woman Citizen,” in Women’s America, 8th ed. Linda K. Kerber, Jane S. De Hart, Cornelia H. Dayton and Justy Tzu-Chun Wu (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

These shifts, along with the notion of separate spheres, allowed women to access the profession of teaching as an “extension of mothering,” in which women were seen as uniquely equipped to instill moral values in and provide care to children in a setting that mirrored the domestic home.6Hoffman, Inquiring, 107. This newfound ability of women to access teaching as one of the few legitimate careers open to them was clearly shown in the story of Mrs. William A. Holt, who established the first secondary school for girls in Davidson in 1860.7Shaw, Cornelia Rebekah. Davidson College: Intimate Facts. William J. Martin. New York: Fleming H. Revell Press, 1923. 116.

Music as Access to Academia

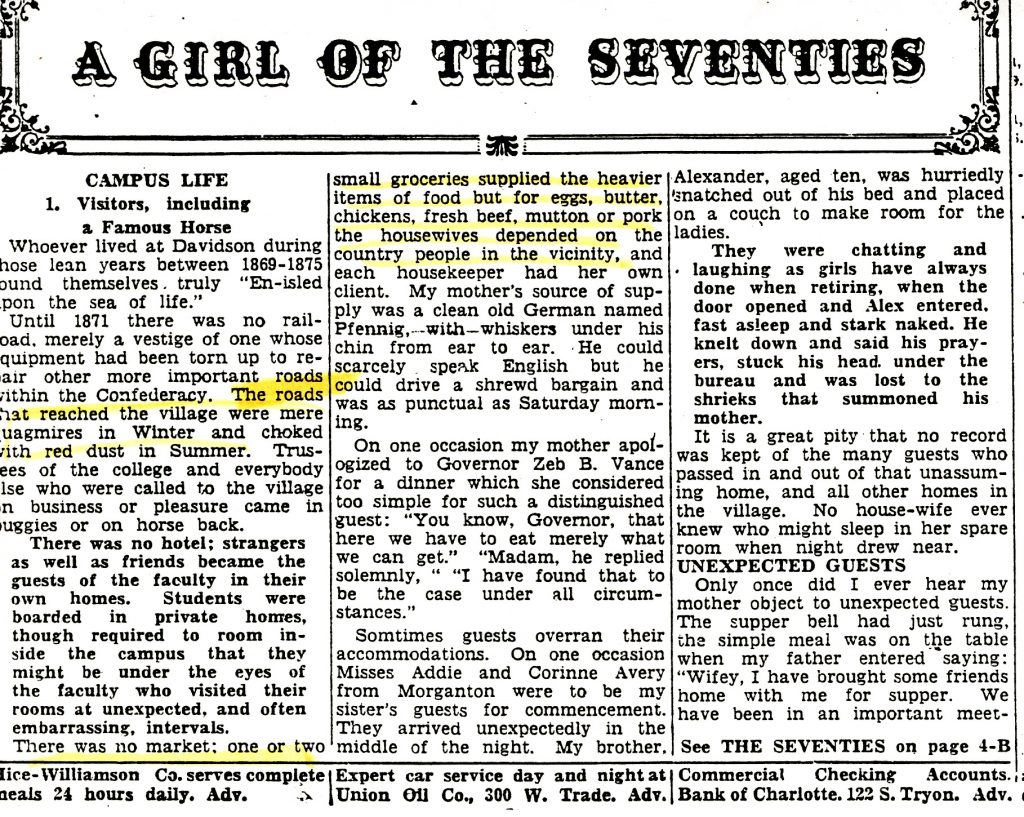

While white Southerners expected respectable women to confine their labor to their homes and families, musical performance played an important role in early Davidson as an entry point into the public sphere for women and a source of entertainment for the whole community. The male and female members of the church club made up the choir and also performed for the students in Chambers, the main academic building at Davidson College.9Jan Blodgett and Ralph Levering, “One Town, Many Voices” (Davidson: Davidson Historical Society, 2012) 53.

In southern society, music also allowed nineteenth-century women to access income as teachers. Southern white women of the upper class traditionally had access to music instruction, a talent seen as desirable in a spouse. Middle-class families aspired for their daughters to have such skills, too. For this reason, women who worked as educators often taught music because doing so conformed to gender norms and did not challenge the widely held belief that women were incapable of teaching subjects that required reason and logic, like math or science. Mary Brown Hinely, a piano instructor and choral director in Georgia, argues that the progress of women’s opportunities within American music parallels that of women’s progress within American society.10Hinely, Mary Brown. “The Uphill Climb of Women in American Music: Performers and Teachers.” Music Educators Journal 70, no. 8 (1984): 31-35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3400871.

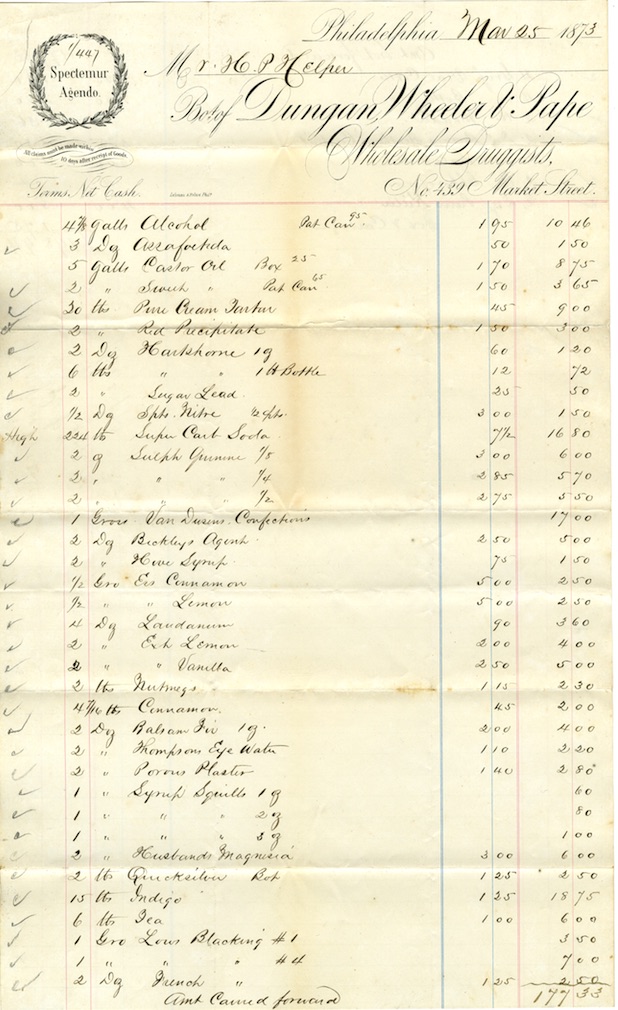

Eulalia V. Cornelius was a music teacher who taught piano and singing lessons in Davidson. Because music lessons were an extra expense in an economically volatile period, these women likely taught children of middle- and upper-class families.11Kim Tolley, “Music Teachers in the North Carolina Education Market, 1800-1840,” Social Science History, no.2 (Spring 2008): 85,http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0145553200013936. In the 1900 census, Eulalia Cornelius’ profession is not listed; only her husband’s profession, cradle-making, appears. That a census-taker obscured her skill and profession is not surprising; excluding women’s paid work emphasized the “distinctive male claim to the role of the ‘breadwinner’” that characterized the period. 12 Boydston, Pastoralization, 134. Nonetheless, Cornelius’s recital pamphlet makes it clear that she had a profession and generated income.

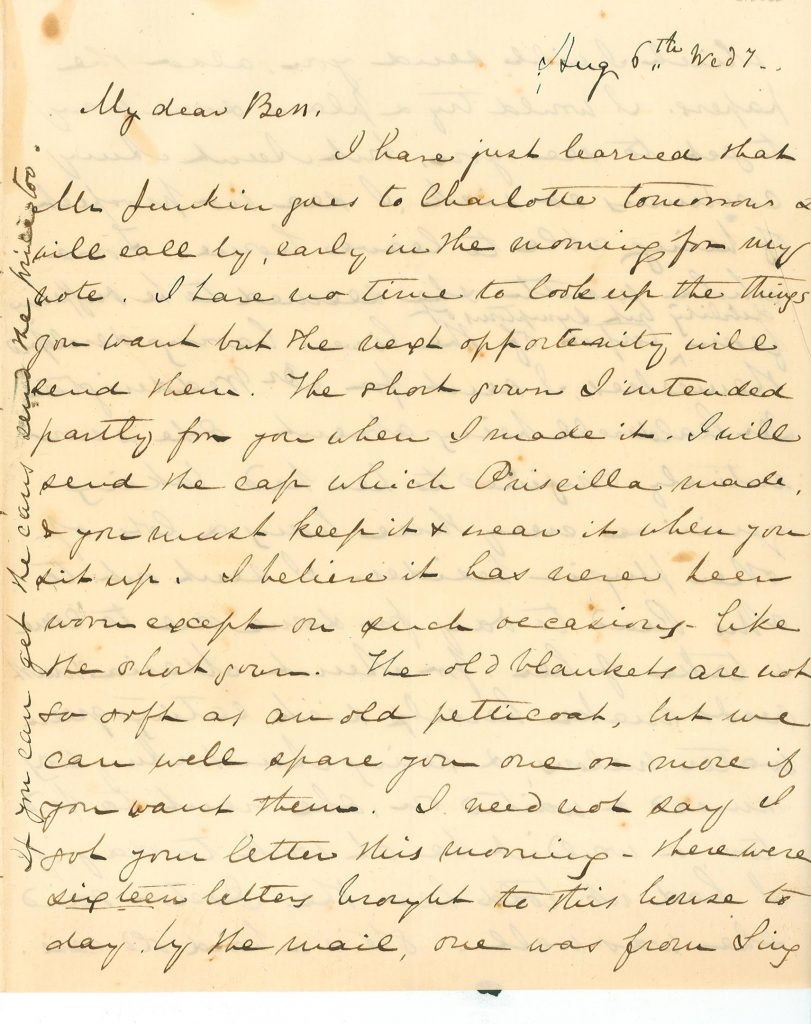

Though music classes were not incorporated into North Carolinian school curriculums until the latter part of the 1800s,15Tolley, 89. women who were music teachers earned income before this period, some of which could support their families. In an 1869 letter, Davidson resident Ann Mills wrote to her niece Ella about her professional prospects. She explained that several parents asked her to teach their children and included the wages they offered her. Mills explained: “I will teach and be glad of the chance, for I can help my family more by teaching than any other way.”16Ann M. Mills Letter, 1869, Davidson College Archives and Special Collections. The inclusion of the rates offered for her teaching capabilities suggests that neighbors compensated and acknowledged women’s labor–even when officials and census-takers did not. This is a cautionary reminder that singular historical narratives told by government documents, like the census, underestimate the importance of southern women’s paid, and unpaid, labor in the nineteenth century.

In late-nineteenth-century Davidson white, middle-class women expanded the domestic, maternal sphere to include certain paid jobs. Teaching music became an accessible way to participate in public life while also fulfilling the idealized feminine role of educating and raising moral children.18 Therefore, through teaching music, white women in Davidson were able to leverage the expectations of domesticity and motherhood. While excluded from the faculty of the college because of their gender, records in the Davidson College Archive provide evidence that female educators were nonetheless part of the intellectual community here. As teachers and performers, female musicians nurtured young minds and the emerging arts scene on campus.

<

<

<

<