C. Miller and F. Resweber, with I. Padalecki

Until the development of the field of women’s history in the 1960s, historians often limited their analysis of nineteenth-century women’s roles to that of wives and daughters. Listed beneath male heads-of-households on the census and ignored in many common primary sources, women were considered secondary contributors to their families and communities — if historians considered them at all. Over the last fifty years, historians have proven that women and girls were key participants in the workforce and economy, including in the town of Davidson.

Historians have described the lives of nineteenth-century women and men as characterized by an idealized separation of gendered spheres. Known for her innovative research about the economic value created through domestic labor, historian Jeanne Boydston explained that the ideology of separate spheres normalized a system in which men worked for wages in the public sphere and women cared for children and ran households in a private one. Men’s work was valued as skilled labor and given monetary compensation, whereas women’s labor cleaning, caring for children, and preparing food in their homes was uncompensated.1Jeanne Boydston, “The Pastoralization of Housework,” in Women’s America: Refocusing the Past, ed. Linda K. Kerber, et al. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016), 128-29. Despite the ideology of separate spheres, working-class white women and women of color regularly labored in the market economy. They often did so in other women’s homes or turned their homes into income-generating workplaces by taking in laundry or borders, referred to as the accommodations business.2Lucy Eldersveld Murphy, “Her Own Boss: Business Women and Separate Spheres in the Midwest, 1850-1880,” Illinois Historical Journal 80, no. 3 (June 1987). 3Rupert T. Barber, “A Davidson Historical District Walking Tour.” n.d., 16.

The accommodations business was particularly important in nineteenth-century Davidson because town families provided housing and meals to students and faculty. Because men usually owned these houses and businesses, women’s labor in them was often obscured in primary sources. For example, take the Helper family business, founded in 1848.4Rupert T. Barber, “A Davidson Historical District Walking Tour.” n.d., 16. Hanson P. Helper was a prominent businessman who converted his general merchandise store across from Davidson College into a thirteen-room hotel while simultaneously opening a new store and post office on the property. The people of Davidson respected Helper, referring to him as “one of the most highly thought of citizens of Mecklenburg County.5Obituary for H.P. Helper. Charlotte News, October 2. 1902. The Helper businesses were family operations, however, to which his wives (he was widowed and later remarried) and children contributed. By understanding nineteenth-century gender roles and divisions of labor, we can read primary sources about Hanson to learn about Sallie, Martha, the ten surviving children he had with the two women, and the enslaved women who also lived in the household.

Female Labor in the Helper Household

Historical records show multiple female laborers in this household over time, and the evolution of this family’s composition hints at common demographic trends in the mid-nineteenth century South. In addition to Hanson, the 1860 census lists one adult woman, Sallie, as well as two children and an unrelated male laborer.7U.S. Census Bureau, “Schedule I, Free Inhabitants in Mecklenburg, NC,” 1860. Hanson also leased three enslaved people, including a twenty-five-year-old woman and a twelve-year-old girl, evidenced in the 1860 slave schedule. 8 U.S. Census Bureau. Slave Schedule, 1860.This leasing arrangement may have accommodated the seasonal nature of the family’s hospitality business. Slave schedules do not include the name of the enslaved people, a reality that frustrates historians and makes research challenging. Additionally, by separating enslaved and free women onto two documents, the documentary record makes invisible the collaboration required between enslaved and free white women to complete essential domestic labor.

By 1870, Hanson had remarried to Mattie (presumably after the death of Sallie), and they were parenting five children between the ages of twelve and one years old.10U.S. Census Bureau, “Schedule I, Mecklenburg, NC,” 1870. The family continued to grow by the 1880 census as son John had moved out of the household while Mattie and Lillie, Hanson’s eldest daughter by Sallie, continued to care for the remaining children. Another young man also worked and boarded with the family.11U.S. Census Bureau, “Schedule I, Mecklenburg, NC,” 1880. Though we cannot know for sure why John left while the Helper’s female children stayed, we can infer that the demand for their domestic labor to keep the Helper business running did not lessen simply because these children became adults. Ultimately, that these women were still listed under Mr. Helper’s household in the 1880 census demonstrates remarkable stability, even through Sallie’s probable death, in a familial structure in which the Helper’s home and business both relied on the daily, domestic labor of women.

Though the Helper business is recorded and therefore remembered as the property of Hanson Helper, women’s labor was essential to the creation and running of this business.This is because coverture, the dominant gendered legal system during the period in which the Helper’s ran their business, allowed a husband total control over his wife’s body, wages, and any property she inherited..12Linda K. Kerber, “Why Diamonds Really Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 153, no. 1 (March 2009), 60. Because of this, anything Sallie or Mattie Helper produced would have been listed in Hanson Helper’s name. This is why many women, with few exceptions of “keeping house,” are listed as lacking occupations in the 1860, 1870, and 1880 census. Census takers likely focused on obtaining an accurate count of women’s children—emphasizing their reproductive worth. Much of the labor these women and their daughters performed in the family store is effectively missing from the record.

Because it is almost impossible to track the trajectory of each Helper woman, we investigate the collective roles the women played in the household, store, home, and community. We do not know who performed which tasks, but enslaved women usually performed the heaviest labor in Southern households. In a typical week, these women and girls were responsible for a variety of tasks in the home.13Susan Strasser, Never Done: A History of American Housework (New York, NY: Pantheon, 1982).Sallie and later Mattie, their daughters, and enslaved women and girls prepared and preserved food, likely purchasing raw goods from nearby farmers to do so while selling some in the family store.14Jan Blodgett and Ralph B. Levering, One Town, Many Voices: A History of Davidson, North Carolina (Davidson, NC: Davidson Historical Society, 2012), 13 Enslaved women likely did the hard, manual labor of chopping wood, building fires, and pumping water for each meal. The endless work needed to feed family members, employees, and hotel guests is often overlooked in the historical record.

Women were also responsible for laundry, sewing, and ironing. The Helper women likely made some of their clothes, as their store sold fabrics and sewing materials.15Linda English, “Revealing Accounts: Women’s Lives and General Stores,” Historian 64, no. 3/4 (Spring/Summer 2002). Clearly, the work of “running the household” required a wide variety of skills and talents, despite that it was undervalued as an unskilled, inherent component of womanhood that did not merit monetary compensation.

The Helper Businesses

The Helper Hotel existed at the intersection of women’s domestic labor and the male-dominated market economy. Hotels were commonly owned by men, but the upkeep was largely considered women’s work.16Wendy Gamber, “Tarnished Labor: The Home, the Market, and the Boardinghouse in Antebellum America,” Journal of the Early Republic 22, no. 2 (Summer 2002). Although not documented, most of the domestic labor in the hotel was performed by Helper’s wife, older daughters, enslaved women before emancipation, and potentially hired servants after the war: they washed, cleaned, and cooked. Helper’s literate daughters potentially worked in the store and could have assisted in record keeping, as women in mercantile families commonly did.17Gamber, “Tarnished Labor,” 179.

Though the Helpers employed a live-in male clerk via the 1870 census, the store’s success in town suggests that Mattie and the older daughters likely worked the counter of the store alongside hired employees.19U.S. Census Bureau, “Schedule I, Free Inhabitants in Mecklenburg, NC,” 1870. The Helper women facilitated purchasing, wrapped packages, and used the store as an outlet to connect with community members. It is not known exactly how much this labor was worth, but a nineteenth-century woman working as a clerk in the Midwest made about thirty dollars a month—demonstrating that the work of the Helper women was of high economic value, even if they were never paid.20English, “Revealing Accounts,” 572.

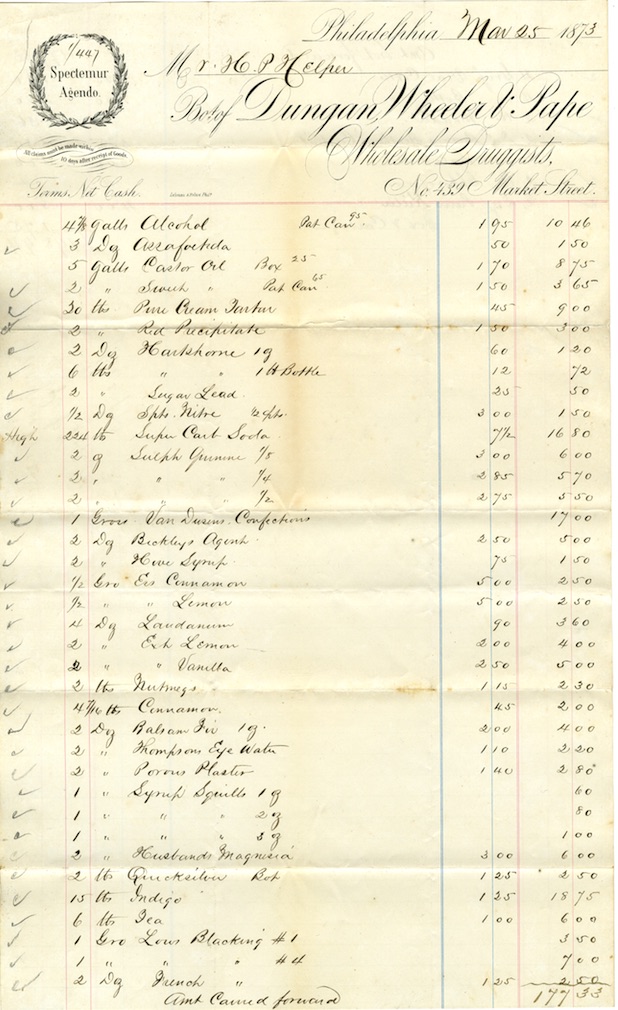

Davidson College and the store maintained good relations—students recalled fondly Mr. Helper’s kindness and intelligence.21Chalmers G. Davidson, “Lives of the Wayside Inn,” The State, November 15, 1971. Davidson College Archives, Davidson, NC. Davidson College also accepted a loan from Mr. Helper as they rebuilt after the Civil War.22Blodgett and Levering, One Town, 44. Further, while the college launched lawsuits against local businesses for selling alcohol to students, there is no record of such a lawsuit against the Helper business, despite that store ledgers indicate the sale of alcohol in the Helper store in 1873. The Helper store and the women who worked there provided important services, products, and community to Davidson College students.23Blodgett and Levering, One Town, 10.

Although the domestic labor of the Helper women was unpaid and left unrecognized in that only their Hanson’s name was legally attached to the business, it was not unimportant. Rather, the lack of pay and historical recognition attributed to the Helper women reflects a broader devaluation of the work associated with womanhood. In recognizing their work, agency, and skill, we can trouble the historical master narrative that seeks to make their contributions to the Davidson community invisible.