E. Conklin, A. Kilby, E. Nagy-Benson, with I. Padalecki

In the Antebellum period, slavery played an integral role on plantations and in households near Davidson College. Although the college itself never owned slaves, prominent men associated with the institution did, including the third college president, Drury Lacy. In her letters preserved by the Davidson College Archives, Drury’s wife Mary described her relationship with the enslaved people in their household. These letters suggest that Mary relied on the labor of enslaved people to accomplish domestic tasks, raise her children, and host college guests. White women like Mary had a direct role in the institution of slavery. Therefore, an analysis of free white women’s relationships with enslaved Black women in their households can provide insights into gender, race, and power in early Davidson.

Experiences of White, Slave-Owning Women

In the mid-nineteenth century American South, privileged white women led lives centered around domesticity. According to the ideal of “separate spheres,” men and women were expected to occupy different spaces and positions in society. As historian Jeanne Boydston explains about nineteenth-century gender roles, “The contrast between Man and Woman melted easily into a contrast between workplace and home:” a wife was expected to create a domestic haven for her husband, who worked in the morally ambiguous public.1Jeanne Boydston, “The Pastoralization of Housework,” in Women’s America: Refocusing the Past, ed. Linda K. Kerber et al (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 128-139. Through this “cult of domesticity,” nineteenth-century Americans idealized white feminine behavior as pious, pure, domestic, and submissive2Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860,” American Quarterly 18, No. 2 (Summer 1966): 151-174

Mary performed these idealized gender norms as a white, Southern woman of means. Her letters show that her daily experiences revolved around child-rearing, cooking, and household management.3Mary Lacy, The Mary Lacy Letters, 1856-1859, https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com/introduction/. At the same time, because Mary’s husband owned enslaved people, she relied on enslaved Black women to complete some domestic work. Because Black women and girls performed household labor and helped care for her children, Mary had time to devote attention to tasks like entertaining high-profile guests of Davidson College.4Catherine Clinton, The Plantation Mistress: Woman’s World in the Old South (New York: Random House Inc, 1982), 19.

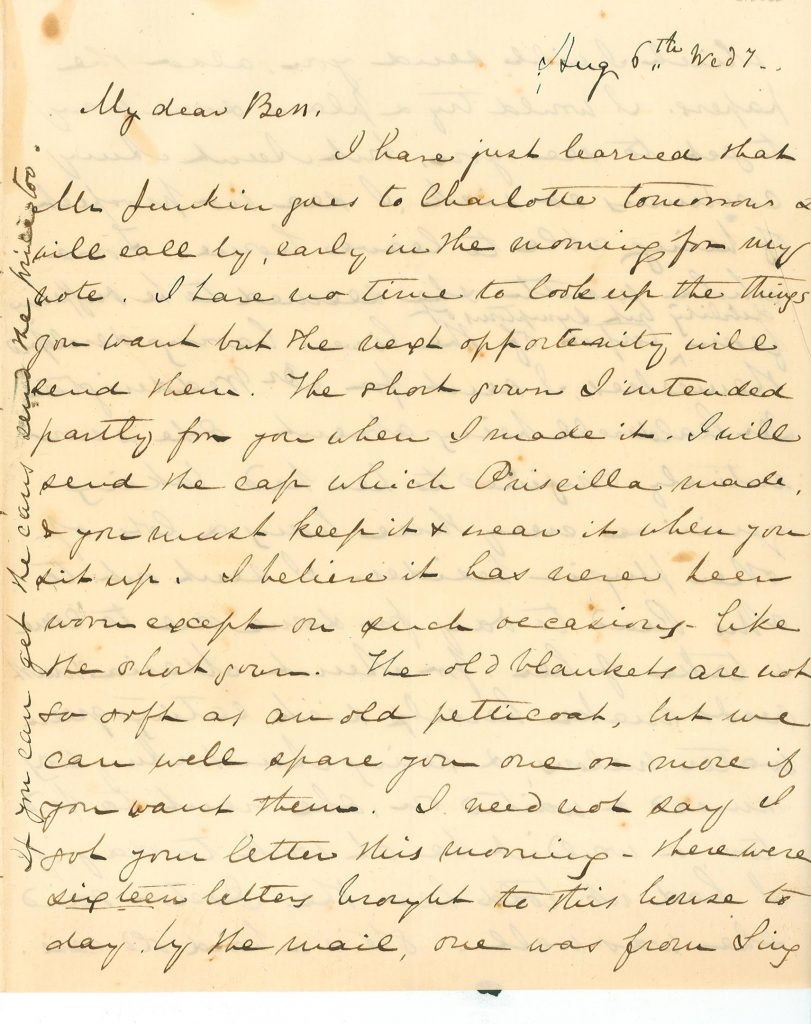

This racialized division of labor reflected privilege and necessity. According to historian Catherine Clinton, mistresses depended on enslaved women’s knowledge and skill because “Southern women [of the slave-owning class] were seldom trained to keep the house.”5Ibid., 49. Mary, whose father was a pastor at Princeton College, was raised in an affluent household and likely learned to manage others’ labor rather than complete unpleasant tasks herself.6“Introduction” The Mary Lacy Letters. https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com/introduction/ (accessed November 6, 2019). Mary made light of her limited skills, writing: “Fishburne7a Davidson professor says I am a ‘model housekeeper’ which tickled me vastly, as your Father says I am one of the poorest.”8Mary Lacy to Bess Dewey, August 6, 1856, in “The Mary Lacy Letters,” https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com/introduction/. Her ability to force enslaved people to do the monotonous tasks of cleaning her family’s house and clothing and growing and preparing their food enabled her to live as a woman of status.

Relations Between White and Enslaved Women

In addition to the housework they performed, enslaved Black women served as primary caregivers to their white mistresses’ children. One of the most common tropes in historical fiction is the “Mammy” figure, an older, matronly Black woman who cared for the plantation mistress and her children. Clinton objects to the “Mammy” figure, saying that it was “created by white Southerners to redeem the relationships between black women and white men within slave society.9Catherine Clinton, The Plantation Mistress: Woman’s World in the Old South (New York: Random House Inc, 1982), 48. The nickname “Mammy” dehumanized enslaved women and suggested their willing participation in the forced labor of raising the children of their mistresses rather than their own. It also enabled slave owners, like the Lacys, who actively sought to buy a child from a nearby plantation, to deny their role in family separation.10Emily West and R.J. Knight, “Mothers’ Milk: Slavery, Wet-Nursing, and Black and White Women in the Antebellum South.” Journal of Southern History 83, no. 1 (2017): 37-6.

In a letter from August 6, 1856, Mary referred to two enslaved women, Amy and Maria, as “Aunt.” These familial terms obscure the true nature of their relationship. Mary’s language is laced with condescension, stating that she would like to leave home, but “Aunt Amy continues so sick” that she (Mary) had to take on more household labor. She suspects another slave, Maria, of faking illness to avoid working.11 Mary Lacy to Elizabeth Lacy, August 6, 1856, in “The Mary Lacy Letters,” https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com/introduction/. Historian Stephanie Camp explains that although enslaved people suffered from sickness and pain resulting from overwork, malnutrition, and a lack of medical care, enslaved women sometimes did rebel against their owners using one of the few safe methods available to them: feigning illness. These subtle acts disrupted households and asserted enslaved women’s humanity.12Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 36

Notably, white women often claimed ownership of enslaved people. Because of coverture laws that legally subsumed wives to their husbands, married women could not independently own land until well into the nineteenth century. Widows retained a portion of the property for their use, but sons inherited their father’s land. For this reason, many fathers willed enslaved people to their daughters. In the will of Hezekiah Alexander of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, written in 1796, he gave his wife “two negro men named Sam and Abram.”13Hezekiah Alexander Last Will and Testament, August 8, 1796, Davidson College Archives In a will from the Castanea Grove plantation near Davidson, a husband chose not to will his wife enslaved people because “my wife has enough [enslaved people] of her own.”14 Hezekiah Alexander. A Copy of the Last Will and Testament of Hezekiah Alexander. 8 August 1796. DC058. Chalmers Davidson – Plantation Files. Davidson College Archives, Davidson, North Carolina. These documents demonstrate that privileged white women directly maintained the institution of slavery.

White Women and Discipline

Although we typically associate the disciplining of enslaved people with white men, white women learned to enforce power and control over enslaved people from youth, when slave-owning parents gifted enslaved people to young girls. Historian Stephanie Jones-Rogers notes, “young white girls came to realize very early on that they could own and control other human beings.”15 Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, “Mistresses in the Making: White Girls, Mastery and the Practice of Slaveownership in the Nineteenth-Century South,” in Women’s America: Refocusing the Past, ed. Linda K. Kerber et al (New York: University of Oxford Press, 2016), 145. Trained to punish by their mothers, white women became the main source of discipline for enslaved people within the house.

According to the gendered and racialized hierarchy of slave-owning households, slave-owning women were submissive to their husbands yet violent towards enslaved people. Historian Thavolia Glymph argues that slave-owning women normally physically coerced and punished slaves.16Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of The Plantation Household (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008) Because the main gendered role for wealthy, slave-owning white women was to serve as moral keeper of the household, they were also expected to discipline enslaved people who challenged patriarchal norms. This transformed the seemingly family-centered household into a violent space for enslaved women. Contrasting presentations of slave-owning women as charming belles in modern popular culture, primary sources from the Antebellum era described discipline by white women as violent and painful for the enslaved.17Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of The Plantation Household (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008). Regarding a case in the town of Davidson wherein an enslaved man was suspected of a crime, Mary praised violence against enslaved people, hoping it would “strike terror into the negroes.”18Lacy, February 1859. Mary’s status, like that of other slave-owning women, came at the expense of enslaved Black people.

Beginning in 2017, Davidson College began to publicly address its complicity with slavery and segregation. The Commission on Race and Slavery prompted interrogation of the college’s role in fostering white supremacy and enabling the exploitation of generations of Black people who worked for the college while denying others an education. The 2020 report acknowledged the role not just of college presidents, faculty, and students, but of the broader college community, including white women, in this. Documents from the college’s archives make clear the intersection between enslavement, white supremacy, and nineteenth-century gender roles, and although gender norms limited white women’s power in relationship to white men, enslavement normalized their ownership and coercion of Black people, particularly the women and girls who worked in their households.