M. Bursis, C. Clawson, and H. Maltzan, with I. Padalecki

Reverend Robert Hall Morrison was the first president of Davidson College, founded in 1837. He and his wife, Mary Graham Morrison, raised twelve children in a white, upper-class Presbyterian household shaped by the belief in God-given separate spheres. Under the ideology of separate spheres, a gendered social hierarchy delineated the roles of men from women. Understood to be morally pure, women were expected to perform uncompensated domestic labor while their husbands worked within the public sphere of civic life, including higher education and the ministry.

As wives and mothers, women had a role to play in preparing boys for this work, and the Morrisons’ commitment to education extended beyond Davidson College; four of the six Morrison daughters attended Salem Female Academy, a Moravian boarding school.1Information about Salem Female Academy courtesy of Salem Academy and College Archives. The Morrisons also owned slaves. A close study of the Morrison family including slave ownership, female education, and their participation in the Presbyterian church enables us to understand the experiences of women at Davidson College during its founding years.

The Morrisons and Slavery

Representative of Antebellum North Carolina in general, Davidson College existed in a world dependent on human bondage and exploitation. Although census statistics show that under seven percent of the free population owned slaves in nearby Alamance, Orange, and Wake counties, historian Daniel Fountain explains that this statistic obscures the widespread influence of slavery in the region.2Daniel Fountain, “A Broader Footprint: Slavery and Slaveholding Households in Antebellum Piedmont North Carolina,” The North Carolina Historical Review 91, no. 4 (October 2014): 410. Fountain looks not at slave ownership but instead at slave-owning households and their economic impact.3Fountain, 407. Under his definition, the share of free people regularly interacting with enslaved people and benefiting from their labor jumps to nearly one out of every three white North Carolinians.4Fountain, 411. Members of these slave-owning households constituted the Antebellum elite, including the president and several professors of the University of North Carolina. It is important to note this intersection between higher education and slave ownership.5Fountain, 414.

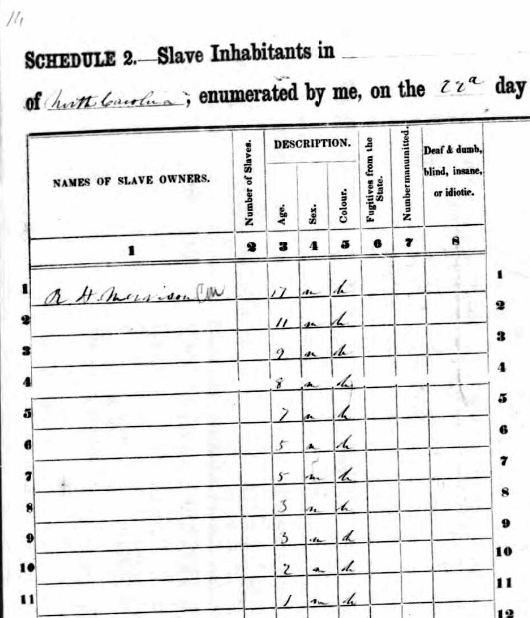

In Mecklenberg County, the influence of slavery was likely even more pervasive. Historian Thomas Hanchett estimates that, although less than one percent of the county’s population were planters–claiming ownership of more than two hundred enslaved people–twenty-five percent of the population claimed ownership of at least one enslaved person.6Thomas W. Hanchett, Sorting out the New South City: Race, Class, and Urban Development in Charlotte, 1875-1975 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 17. By the 1850s, forty percent of the county’s residents were enslaved people.7Hanchett, 17. The Morrison family participated directly in and benefitted from this system. In 1850, Robert Hall Morrison claimed ownership of fifty-three enslaved people.8U.S. Census, 1850.

<

<In this context, the Morrison women navigated dual identities as both privileged slave owners and women subject to the legal system of coverture, in which women could not have legal identity or property independent of their fathers and husbands and were barred from many professions. Despite broader limiting gender norms, slave ownership made life easier for the women of the Morrison family by freeing them from the most monotonous and unpleasant household labor. Historian Drew Gilpin Faust describes white planter women as members of “a society that had privileged them as white yet subordinated them as female.”10Drew Gilpin Faust, Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1996), 7.

White Presbyterian Women

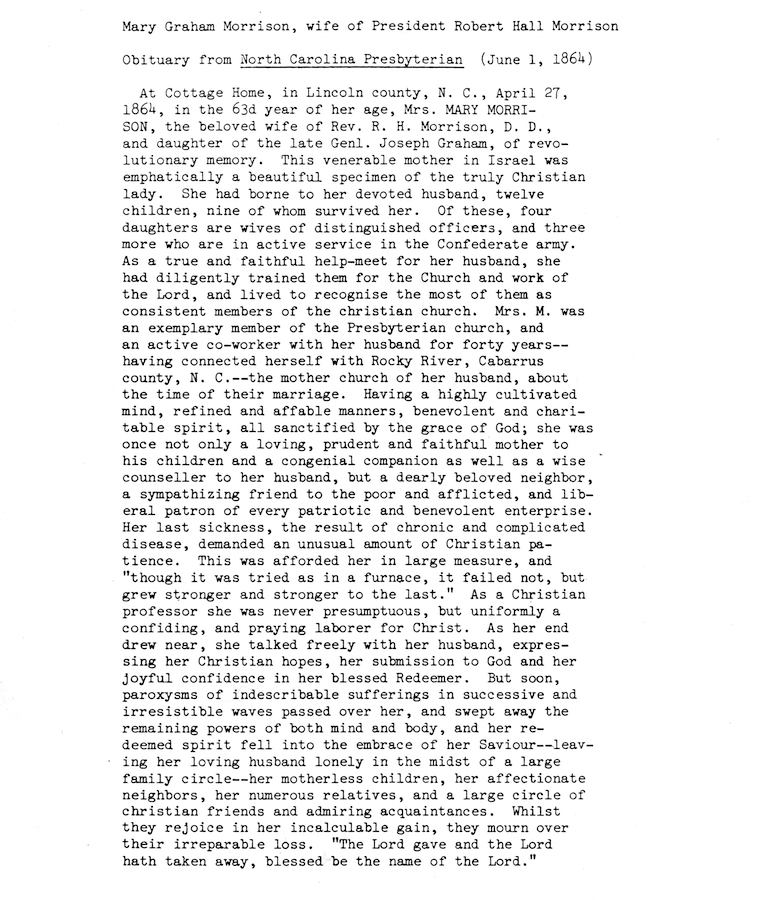

While the ideology of separate spheres encouraged women in the Antebellum South to focus on domestic labor, wives of Presbyterian ministers (including Mary Graham Morrison) also held a public role in the community. In this period, “Cent Societies” or “Praying Societies” provided social opportunities and raised money and support for the Church.11Janet Harbison Penfield, “Women in the Presbyterian Church—an Historical Overview,”Journal of Presbyterian History (1962-1985) 55, no. 2 (1977), 108-109. The development of regional and national women’s boards of home and foreign missions also started around the Civil War.12Penfield, 110. Though Presbyterian leadership prevented women from becoming ministers, they found authority and leadership in organizations such as the Women’s Union Missionary Society of America for Heathen Lands.13Penfield, 110-111. Ministers’ wives, in particular, held power because their husbands and churches saw them as useful in turning other women into more active church members and in welcoming outsiders. 14Lois A. Boyd, “Presbyterian Ministers’ Wives—A Nineteenth-Century Portrait,” Journal of Presbyterian History (1962-1985) 59, no. 1 (1981), 3-5.

Antebellum Education for Women

Because slave-owning families like the Morrisons depended on enslaved women to perform domestic labor, their daughters had greater access to education than the daughters of yeoman families. While the Civil War overall had “a devastating effect on higher education in the South” for men, young women’s schools flourished.15David Silkenat, “‘In Good Hands, in a Safe Place’: Female Academies in Confederate North Carolina,” The North Carolina Historical Review 88, no. 1 (2011), 40. Formal education for women in the Antebellum South consisted of academics as well as religious instruction, sewing, and “polite culture.”16Christie Farnham, The Education of the Southern Belle: Higher Education and Student Socialization in the Antebellum South (New York: New York University Press, 1994), 124-126. Historian Christie Farnham explains that “parents never intended for [female students] to work outside the home”; thus, southern girls’ education largely enforced traditional, patriarchal gender roles and prepared these girls for lives as wives and mothers of promising young men.17Farnham, 3. This accurately depicts the Morrison family women. Mary Graham Morrison attended Salem Female Academy from 1815 to 1816, and her daughters each attended the academy, married prominent men, and raised children.

Salem Female Academy had a progressive curriculum for the early-nineteenth century, according to historian Frances Griffin.19Frances Griffin, Less Time for Meddling: A History of Salem Academy and College, 1772-1886 (Winston-Salem: John F. Blair, 1979), 101. ineteenth-century students took courses in a variety of academic and artistic subjects, including “Writing, Arithmetic, […] Botany, Algebra, […] Drawing and Painting.”20 Information courtesy of the Salem Academy and College archives, retrieved from the earliest Salem Female Academy course catalogue in 1853. It is safe to assume that the curriculum was largely the same in the 1850s as it was during the time that the Morrison women attended the Academy. Students had strict schedules, and “any so-called ‘free’ time was to be used for plain sewing, ‘marking’ (pattern making), or knitting.”21Griffin, 102-103. Reflecting the institution’s commitment to reinforcing traditional gender roles, Salem did not accept girls who were over fifteen years old, as this was “marrying age.”22Information courtesy of Salem Academy and College archivist Terry Collins.

<

<This curriculum contrasts from that at all-male Davidson College. According to the 1842 course catalogue, all students in the same academic year took the same courses, including subjects like “English Grammar, Arithmetic and Geography,” and “Latin Grammar, Mair’s Introduction, Caesar’s Commentaries, and Virgil.”24Catalogue of the Trustees, Faculty and Students, of Davidson College, 1842. Charlotte: The Charlotte Journal, 1842. Davidson offered its male students fewer extracurriculars and focused on classical studies, while Salem provided its female students with creative classes and a broader selection of academic courses.

Several of the Morrison daughters married educators who became Confederate generals during the Civil War. Mary Anna Morrison became the second wife of Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson.26“Mary Anna Morrison,” Family Search. Isabella and Eugenia also married Confederate generals, D.H. Hill, a Davidson College professor, and Rufus Barringer, respectively.27“Isabella Sophia Morrison,” Family Search. “Eugenia Erixene Morrison,” Family Search. Recognizing that race and class shaped women’s experiences as much as gender, the documentary record provides insight into how elite Southern white women were socialized and why they supported the Confederate war effort. Born into lives of prominence and respectability, women from slave-owning white families sought to maintain the privilege and status to which they were accustomed. Records of enslavement caution us against romanticization, however. It is important to recognize that here, as elsewhere in the Antebellum South, elite women exploited the labor of enslaved women whose names do not appear in the records of the household and college their labor sustained.