A. Turner and T. Bohannon, with I. Padalecki

Davidson College’s official history emphasizes the contributions of early trustees, presidents, and faculty in establishing the college, but neglects those of women. Although excluded as students and denied employment as faculty, women worked all over campus, particularly cleaning and preparing food for students, faculty, and staff. By analyzing U.S. census data, letters, and diaries left by women who lived on or near campus, historians can imagine what free and enslaved women’s culinary work might have looked like in nineteenth-century Davidson.

Food in Early Davidson

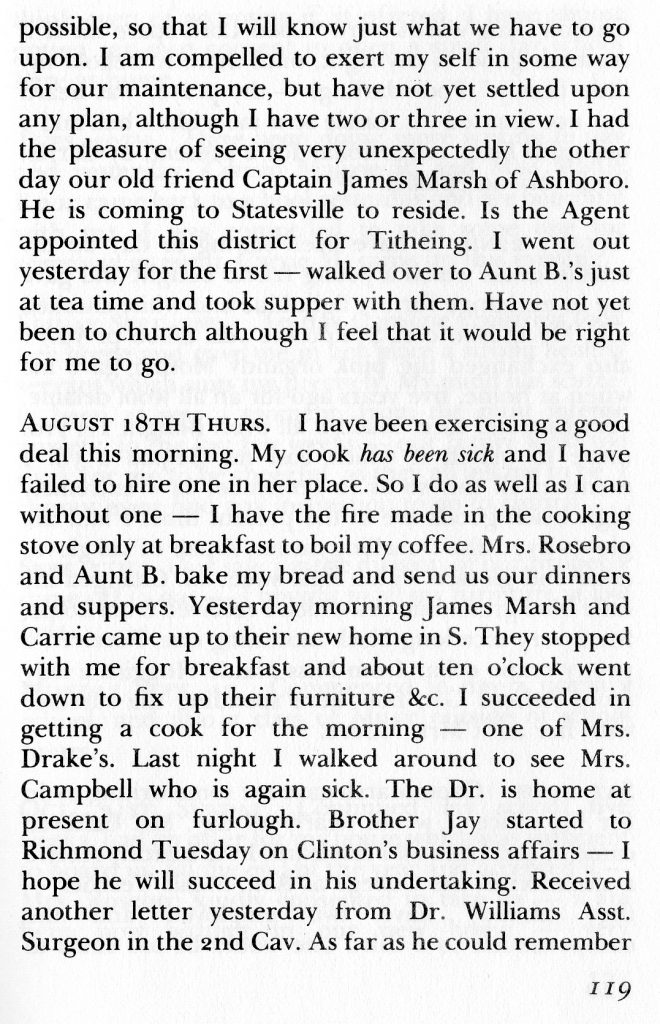

While North Carolina plantations and farms mass-produced food like corn and pork for sale at markets, most people, white and Black, produced some of their own food. Residents of small towns like Davidson grew vegetables and raised livestock in their own yards.1Christopher Farrish, “Food in the Antebellum South and the Confederacy” in Food in the Civil War Era: The South, edited by Helen Zoe Veit, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2015) 3, 7; Jan Blodgett and Ralph B. Levering, One Town, Many Voices: A History of Davidson, North Carolina (Davidson College Historical Society: Davidson, 2012), 27. In her diary, Ellie M. Andrews, a white woman from nearby Statesville, discussed her family’s vegetable and poultry production.2Ann Campell Mac Bryde, Ellie’s Book: Being the Journal Kept by Ellie M. Andrews from January 1862 through May 1865, (Davidson: Briarpatch Press, 1984). The prices of poultry, eggs, and butter were high at the time, and gardening saved Ellie and her family money. Likewise, Mary Lacy, the wife of the third Davidson College president, Drury Lacy, wrote about the family’s garden in a letter to her stepdaughter, Bess: “How does your garden grow? The sun & drought has ruined our melons…of late they are only fit to feed the pigs.”3 Mary Lacy to Bess, 6 August 1856, from The Mary Lacy Letters, Davidson College, https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com/uncategorized/620/. Mary Lacy also mentioned her celery plants in this letter. It is unclear how large their garden was, but Mary and the family’s slaves, who probably performed much of this labor as was custom in the Antebellum South, grew vegetables and fruit to feed household members and guests of the college.4In her letter to Bess on August 6, 1856, Mary Lacy mentions feeding melon to a sick enslaved woman, Aunt Amy. Enslaved people in Davidson also sometimes had their own small plots of land on which to grow food in order to supplement their diets5Jan Blodgett and Ralph B. Levering, One Town, Many Voices: A History of Davidson, North Carolina (Davidson College Historical Society: Davidson, 2012), 27.

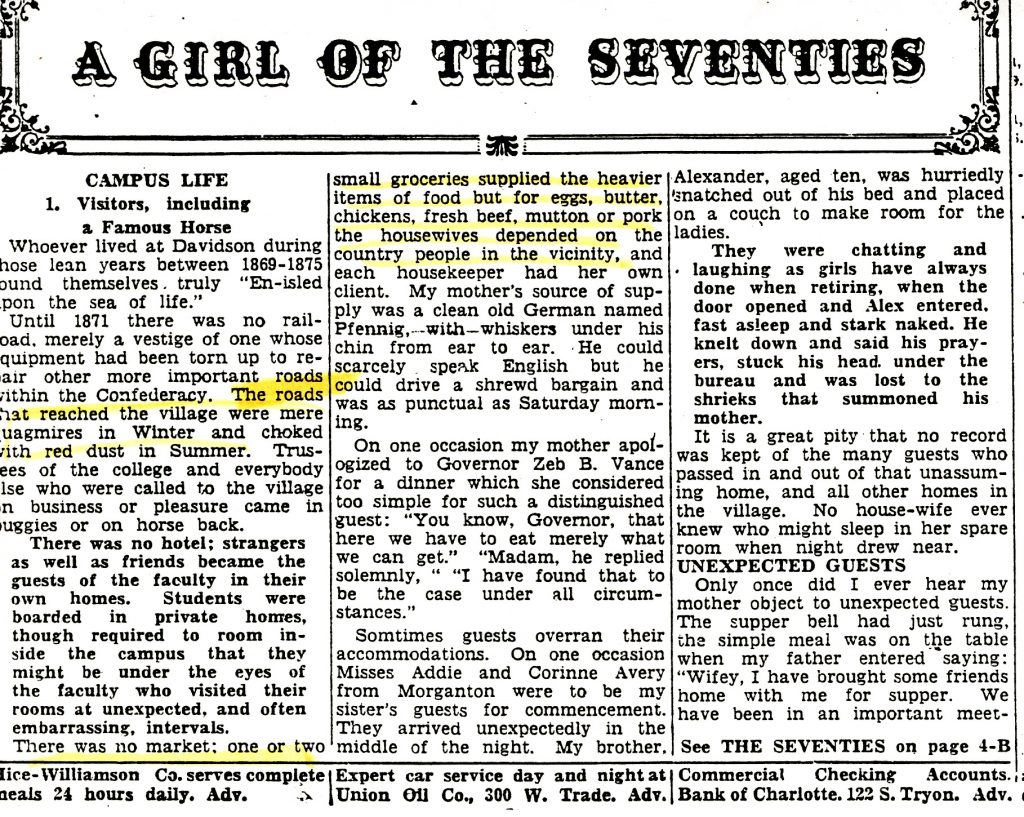

Davidson residents also purchased food at local stores. A white woman who lived in Davidson in the 1870s explained that “there was no market, one or two small groceries supplied heavier items of food, but for eggs, butter, chicken…the housewives depended on the country people in the vicinity.”6“A Girl of the Seventies,” News clipping, Undated, Reminisces—Lucy Phelps Davidsoniana File, Davidson College Archives, Davidson NC, (D-File, “Reminisces—Lucy Phelps Russell). Consequently, Davidson residents enjoyed far fewer culinary choices compared to those who lived in larger cities, like nearby Charlotte.

In another letter to Bess, Mary Lacy inquired about prices of lemons and sugar in Charlotte. 7 Mary Lacy to Bess, 2 July 1856, from The Mary Lacy Letters, Davidson College, https://his306sp17blog.rosestremlau.com/uncategorized/july-2-1856/ Introduced into the Anglo culinary world during the colonial era, cooks used acidic lemons to season and preserve food. While the Spanish extended lemon cultivation into the Americas (specifically in Florida), enslaved people throughout the Caribbean produced sugar, a major cash crop. By the nineteenth century, both lemons and refined sugar were staples of the Anglo-American diet in the South. Prosperous families like the Lacys enjoyed lemon sauces, preserves, and, of course, lemonade. Lemonade, in particular, grew in popularity during the mid-nineteenth century among those who advocated for temperance, or abstaining from alcohol consumption for moral reasons. This included Presbyterians like the Lacys.8 Pierre Lazlo, Citrus: A History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 108-09; Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Penguin Press, 1986). It’s possible that Mary sought lemons and sugar for lemonade for a campus event. It is also notable that she expected Bess to help her shop; nineteenth-century women commonly performed domestic labor, including shopping, for family members and friends who lived in separate households. Women’s networks of shared labor were an important social and economic support and ones that sustained the college.

Food Production and Enslavement

Enslaved women grew and prepared food for Antebellum slave-owning households and for white Southerners, regardless of whether or not they owned slaves. Slave-owning whites who created the documentary record normalized this racialized and gendered division of labor. Because they believed this work to be an enslaved woman’s God-given role, they did not explain it or comment on it except when noting the value of that labor as crops grown or meals consumed. Slave owners rarely characterized enslaved women as essential or skilled laborers although their work sustained households and communities. As a result, many records created by those nourished by enslaved women render those very women invisible. We know everyone in the Antebellum South had to eat, but most primary sources only give us glimpses of the women who prepared that food.

Through an analysis of oral histories with Southern white people who were children before the Civil War, historian David Anderson found that many romanticized the enslaved Black women who cooked for them. They saw these enslaved women as maternal figures who loved cooking for them rather than human beings coerced into forced labor that often subjected them to surveillance and punishment by their mistresses and isolated them from other enslaved people.9 David Anderson, “Consuming Memories: Food and Childhood in Postbellum Plantation Memoirs and Reminiscences,” Food, Culture & Society20, no. 3 (July 2017): 448. Whites raised in slave-owning households fondly remembered enslaved cooks, but they failed to recognize and acknowledge both the violence these women endured and the skills they possessed.10Stephanie Jones-Rogers, “Mistresses in the Making,” in Women’s America, edited by Linda K. Kerber, Jane Sherron De Hart, Cornelia Hughes Dayton, and Judy Tzu-Chun Wu (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 139-141.

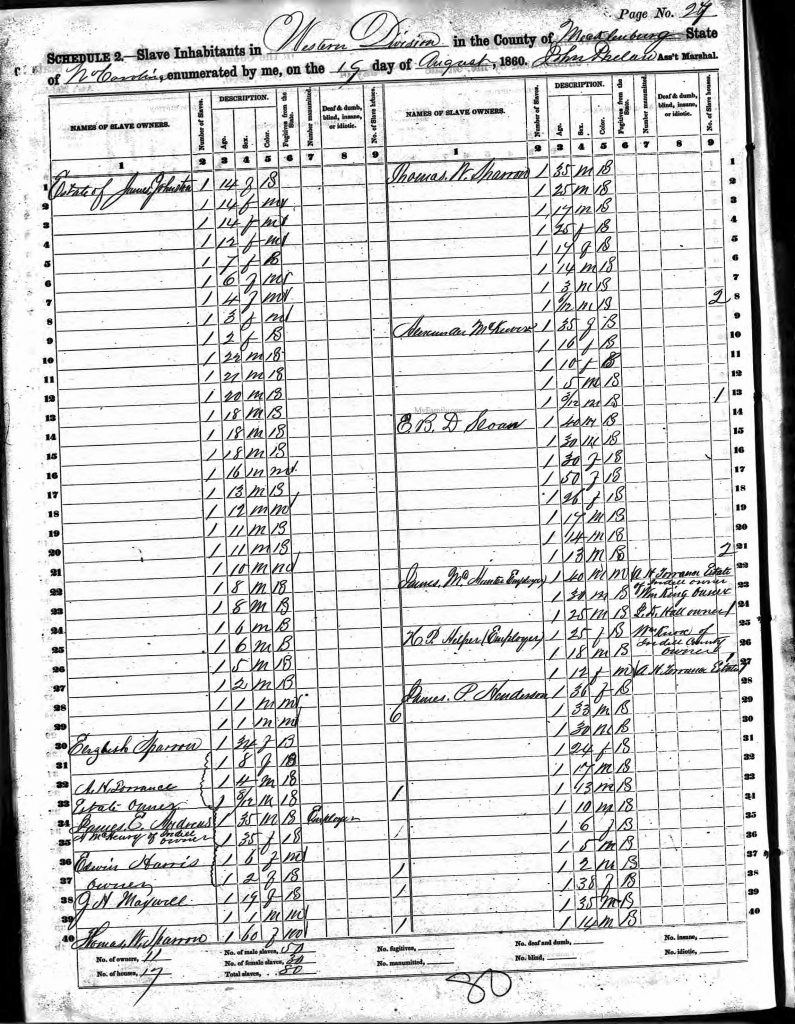

In the nineteenth century, free and enslaved women’s kitchen work was undervalued because it was associated with the uncompensated labor of maintaining the home rather than the economic development and growth of commercial markets. This was true even in cases involving clear exchanges of currency for food, such as when students paid for prepared meals at local eating and boarding houses.11Jeanne Boydston, “The Pastoralization of Housework,” in Women’s America, edited by Linda K. Kerber, Jane Sherron De Hart, Cornelia Hughes Dayton, and Judy Tzu-Chun Wu (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 131. Rather than cooking their own meals or eating in a common cafeteria, students dined on campus at Steward’s Hall and at off-campus boarding houses.12 Jan Blodgett and Ralph B. Levering, One Town, Many Voices: A History of Davidson, North Carolina (Davidson College Historical Society: Davidson, 2012), 13. Data from the 1860 U.S. Federal Census shows that local boarding house owners in Davidson held enslaved women who presumably performed domestic labor benefitting members of the college community. Census takers did not record the names of these women. Did students know them by name? We wonder but cannot know if Davidson College students who interacted with them on a daily basis would have related to them as they did to enslaved cooks back home.13Beaty, Mary D. A History of Davidson College Davidson, N.C: Briarpatch Press, 1988. 82; Ancestry. “1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules.” HeritageQuest Online, 2019.

While they did not acknowledge the economic value of enslaved women’s work, slave owners depended on it for their survival as they lacked the necessary skills or were unwilling to perform this labor themselves. In another diary entry, Ellie M. Andrews complained about having to hire a Black cook: “Today I have hired a cook for the enormous sum of $120.00 and clothe her….[Black people] never were known to hire so high.”14 Ann Campell Mac Bryde, Ellie’s Book: Being the Journal Kept by Ellie M. Andrews from January 1862 through May 1865, (Davidson: Briarpatch Press, 1984). Andrews’ entry demonstrates that white Southerners both diminished and depended upon the domestic labor of Black women. As Black women entered the wage labor market, their newfound freedom — including to negotiate reasonable wages and safe working conditions — proved threatening to their white counterparts. 15Tera W. Hunter, “Reconstruction and the Meanings of Freedom,” in Women’s America, edited by Linda K. Kerber, Jane Sherron De Hart, Cornelia Hughes Dayton, and Judy Tzu-Chun Wu (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 279. However, as much as women like Andrews disliked fairly compensating a Black woman for her work, she and other white women like her depended on this labor to manage their households.16Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 134.

By investigating the history of food preparation in nineteenth-century Davidson, we gain insight into power relations among members of the campus community and the gendered and racialized value system of those who created the documents in our archives. While students, faculty, and staff ate multiple meals each day, women’s work preparing, serving, and cleaning up after those meals was largely ignored as unimportant. When we think today about who prepares our food and how food service enable everything else we do from our normal routine of classes to our celebrations marked by special dinners, we should pause and ask what kind of records we are creating that document the important work of nourishing the college community and the conditions in which our food service staff do these essential jobs.